There is a bridge in Selma, Alabama, that crosses the wide river that shares the state’s name. The bridge is unassuming but it played a critical role in the nation’s struggle for civil rights.

Johnnie Flowers knows the Edmund Pettus Bridge well. He remembers a day half-a-century ago when he was staring at a line of state troopers and white residents, anger in their eyes. He knelt on this bridge in prayer and silent protest. And when the billy clubs began to beat his body and when the tear gas singed his eyes, he bled on it and ran for his life on it. And when he found a safe place to rest and heal, got back on it, determined to get to the other side, to move on to another place. Flowers was just 16 years old.

“We kneeled and then they threw tear gas and started beating people over the bridge. I was part of that march. And then we stayed kneeling until all those black jacks and all those people started beating on the people who had kneeled. They told us to disperse and ‘go back!’"

It was March 7th, 1965, a day that’s become known as “Bloody Sunday,” when Flowers and 600 others attempted to march to Montgomery, Alabama, to protest the murder of civil rights worker Jimmy Lee Jackson, as well as the roadblocks meant to discourage blacks from voting. Things like having to recite the entire Constitution, something many white poll workers couldn't do themselves. The marchers were turned back. That night, no one was allowed to leave Selma.

To understand why a teenager would be willing to sacrifice so much, you only need to be familiar with the Jim Crow South that Flowers grew up in: a segregated society where the scourge of racism reached him even as a child growing up in Uniontown, Alabama, not 30 miles from Selma, where he still lives. As a boy he would go to get an ice cream cone and then be forced to wait at the shop for hours while the white owner talked sports with friends. If he left, Flowers says, he would have been accused of stealing.

Flowers: “You’re not just talking to somebody who marched over the bridge. Because I have that experience of knowing what difference it makes to be able to go over the bridge and to come back and be called all the names, I mean from a little boy…”

Killian: “What names?”

Flowers: “Nigger names. You see. I’ve been there. I’ve been there. Done it.”

Killian: “Even as a little boy?”

Flowers: “Ooh. Don’t mess that up. You heard the ice cream cone. That wasn’t a made up joke. That was real.”

Killian: “They’d call a little boy that word?”

Flowers: “Ohh. From a baby. Ever since I was born I remember being called that name.”

When the TV networks aired scenes of what happened in Selma that day, many Americans were repulsed by the violence shown to peaceful, unarmed civilians. In many ways it was the moment that galvanized the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

Flowers: “They was marching for just the opportunity, to be able to be whatever I want to be. Not that I wanted to be a big deal, but if I did want to be a big deal – you get my point…”

Killian: You could be.”

Flowers: “I could be. And that’s the reason they died. That’s the reason they died.”

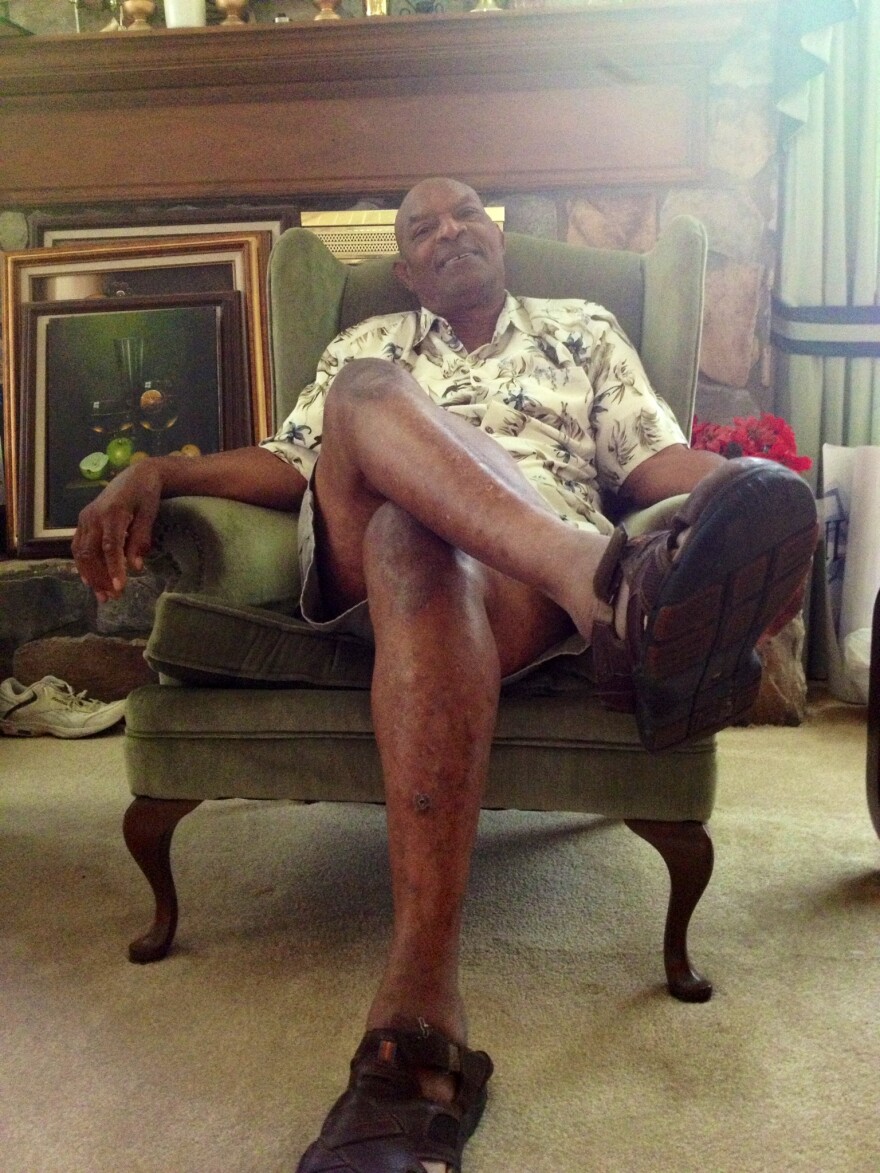

By any measure, Flowers became a big deal. He served in the Air Force and when he was discharged worked, went to night school, and earned a college degree. Then he started his own construction business. Someone said he should run for office and so he did. For almost 20 years he was chairman of the Perry County Commission.

The path over the Pettus Bridge will always run straight through Flowers; be a string that ties the pieces of his life together. He knows that eradicating racism may be impossible and that the struggle will have to be waged indefinitely. After Bloody Sunday there were two more marches, the last one making the 54-mile walk all the way to Montgomery in five days. Flowers was one of the few who walked the entire route. I asked him what he thinks of the movement today, whether he believes it’s being sustained. He answered with a story about a young woman on the march whose feet were so blistered, doctors told her she had to stop walking.

“But they said, ‘Your foot is raw. You can’t.’ She said, ‘I gotta walk!’ A lotta people marched over that bridge with her attitude: ‘I got to do it. I got to do it.’ And a lot of people marched over that bridge without her attitude: ‘Put me in a cart or put me in a car or something where I can ride.’ You got people right now been over that bridge who still want to ride. They want welfare. They want something free. It ain’t free. You got to have her attitude to understand that it’s not about me riding, it’s about me walking.”

Johnnie Flowers moved more than himself when he walked across the Pettus Bridge, the time he went all the way to Montgomery. Down the highway he pushed an idea, a hope for equality, understanding, forgiveness, even love.

Back in Selma, I walk across the span and stop in the middle to watch the river list along far below me. We are all trying to cross the Pettus Bridge, every one of us, to get to the other side of something within ourselves.

Visit Chris Killian's blog.